My return home was a gradual, multi-city one. I flew first to Lima, where I spent one night, and then Toronto, where I spent another. Then, anticlimactically, I took a short morning flight in a prop plane to Cleveland.

At the Cusco airport the morning after Machu Picchu, I felt tired and craved sugar. I saw an older couple in their 70s getting ready to board their flight. The woman had slung a small backpack in front of her chest and another bigger one on her back. I wondered if that could be me and Dan at her age: double-backpacked. I hoped so.

I looked around at the rest of the passengers in the airport. They were nearly all gringos, but they fell into one of two age categories: Either post-college kids in their 20s; or retired people. Where was everyone else? We seem to have this idea in the U.S. that you’re only supposed to travel if you’re young or old. Having kids, I’m sure, plays a big role.

Analog clocks on the wall told the time in cities around the world. Samoa, Los Angeles and Caracas were all broken, the second-hands twitching. The message: It doesn’t really matter what time it is, does it? You’re trapped here anyway.

When I got on my flight and we took off, the plane barely seemed to clear the mountaintops, as if the peaks might scrape the plane’s underside.

I thought about the Inca Trail as we made the short, 1.5-hour journey to Lima. I’d enjoyed it immensely — and I was also certain I was ready for something much harder. Not necessarily physically harder, though maybe that too. But something more emotionally challenging, something where I wasn’t fed so much, literally and figuratively. I’m not quite sure what that is yet, though I have some ideas. I don’t think I would have realized all that if I hadn’t taken this trip.

As we landed in Lima, I felt sleepy, heavy — almost drugged, a combination I’m sure of lack of sleep and the sudden proliferation of oxygen in the air (the Lima airport is only 112 feet above sea level). Suddenly, I was back to getting the same amount of oxygen I get in Cleveland.

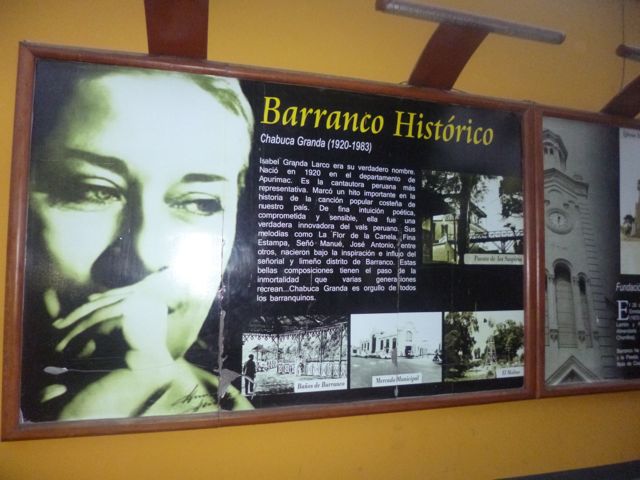

I didn’t find Lima a particularly appealing place. I stayed in the San Isidro district, not far from the airport, in a fine hostal. But I was shocked how car-dependent the city seemed to be — like a South American L.A. At one point, I tried to taxi from my hostal to the Barranco district, where I’d made plans to meet Seth for dinner (he was on a separate flight). Traffic was so slow that I asked the driver to let me out: I could walk faster.

I wended my way through the streets of the tony-but-bland Miraflores district, all shopping malls and mid-rise apartment buildings hugging up to the beach, and reached Barranco right at 6 p.m., when I was supposed to meet Seth. This area, at last, seemed to have some genuine charm.

Including an old square with a lovely church and library.

I saw Seth walking on the sidewalk, and we walked across the Puente de los Suspiros (Bridge of Sighs), a modern plank-board structure that’s nowhere near as romantic as its name, to catch some views of the ocean. Nice to see the Pacific again.

Lima’s bus rapid transit (BRT) system stops in this neighborhood. It bore a lot of resemblance to Cleveland’s Health Line BRT, though seemingly a lot better used. I guess that makes sense given that it seems to be the only official form of public transit in a city of 10 million…

We saw this nighttime market on a vacated parking lot, full of hipsters selling their wares, a band setting up to play. Something like this could work really well in North Collinwood or Detroit Shoreway, I think.

And then our final chifa dinner! I’d found the place, Chifa Chun Yion, online and we had high hopes because people started lining up outside well before dinner opening time at 7 p.m. Also, check out that sign. It has “neighborhood institution” written all over it.

Alas, the food was just OK — Chinese food without the Peruvian spiciness and flare we’d loved at the place in Puno, or that I’d thrilled to on my first night in Arequipa. We ate crepes for desert at a cafe (mmmmmm), and then packed it in for the night. I felt sad saying goodbye to Seth, who’d be staying in Lima another day. We’d been through a lot together over the past few days: A lot of stairs and a lot of smelliness and many amazing sights.

The next morning, I boarded my flight from Lima to Toronto and found myself sitting next to an older man (maybe 60), tall and white-haired and academic-looking, who’d just finished a consulting gig in Peru. He was contracted with the Canadian version of US AID, and his job had been to help Peruvian businessmen meet trade requirements that would help them export their goods to Canada.

I’m usually wary of talking to strangers on planes, but once the two of us got going, there was no stopping. First we talked about quinoa, one of his focus products. Then about how his rental car had been broken into in Lima, his computer stolen. And then pretty much everything else under the sun: Religion, being gay (it turned out he was gay, though he’d been married into his 50s and had two kids), the difficulty and sweetness of relationships. We did take one break in our conversation to watch movies, I “The Impossible” (which I found thoroughly depressing, not in an interesting way) and he “Les Miserables.” But the conversation made the flight seem easy, quick, even though it was 10 hours.

I felt unexpectedly light-hearted setting foot on North American soil when I stepped out of the Toronto airport. I took a shuttle to my hotel, Quality Suites, a once-nice place that had gone to seed (which is why I could afford it). I luxuriated in being to drink tap water and the fact that it was still light out even though it was 8 p.m. I bought some laundry tokens and detergent and gleefully stuffed my travel-dirty clothes in the wash.

On a whim, I Googled “Indian restaurants Toronto airport” and found one 5 km away. I decided to jog there and back to grab takeout, which was cheap and delicious. If you’re ever stuck at the Toronto airport, go to Sweet India or any of the thousand other Indian restaurants around it.

The next morning, I got to the airport two hours early but still managed almost to miss my flight because of the Byzantine queueing system the airport uses to usher people through customs. They make you wait in this big corral-type room until an hour before your flight is scheduled to leave, somehow neglecting the fact that it also takes an hour to get through customs. In the end, the flight was delayed because so many people were in the same boat as me, and I made it back to Cleveland only a few minutes late.

Dan and Vinny and my parents all came together to pick me up. When we got back home, the house seemed a little unfamiliar, a little strange. As if the wood floors were a different color, the furniture in slightly different places, even though I knew everything was the same.

It had worked, I realized. Going away for a month had jogged me from my usual ways of thinking about my life. I hadn’t had a single big revelation, as I had when I’d gone to Guatemala for a month in 2005 and decided to move to Cleveland and start grad school. But my mind was in a new mode, a more objective mode. It was more malleable, more flexible, from having been disrupted.

Dan and Vinny and I went for a walk at Euclid Beach, in North Collinwood. After a month in the mountains and winter, the air felt sticky and hot even though it was cool for this time of year: Only 80. I had that old feeling of Cleveland bittersweetness: How beautiful this place is and also how sad. The old Euclid Beach archway demarcating where an amusement park had once been, a few homeless people, but also the startling blue lake and the surprisingly clean beach and young hopeful-looking people sunbathing. Eventually I realized (or maybe admitted to myself) how tired I was, and we went home to cook dinner — the cheese empanadas we’d learned how to make from Boris in Chile. After that, I showed Dan my photos from the Inca Trail and we looked back at the photos we took together in Santiago and Valparaiso.

We ate more empanadas and talked about all the places we wanted to go. Estonia and Latvia. Colombia. Romania.

I’d done it: Gone to South America for a month largely unsupervised, spent a little more money than was comfortable, taken a million planes and trains and boats and buses with almost no incident or delay.

And now that I was back to my “real” life: Now what?