After discovering my Glanville ancestors had come from Cornwall in the late 19th century — thus explaining my taste for cool weather, Poldark and the Gothic, Cornwall-set tales of Daphne du Maurier (The Birds, Rebecca) — I had two central questions.

What had their lives been like in the old country? And why had they left what by all accounts is one of the most beautiful places in the British Isles, if not in the world?

To find answers, I turned first to Census documents, one of the primary sources of information on Ancestry.com, the enormous, worldwide database of family records.

Maybe this is as good a time as any to explain why the heck Ancestry.com exists.

The answer, in a word, is… Mormons.

Tracing their family history is tremendously important to Mormons.

“We do it,” explains their website, “to obtain names and other genealogical information so … temple ordinances” — such as baptism — “can be performed for our kindred dead. Our ancestors then are taught the gospel in the spirit world and have the choice to accept or reject the work performed for them.”

In other words, genealogical research is the mechanism by which dead relatives can be offered the true gospel of Mormonism — a religion unavailable to anyone born before 1820, when it was founded.

This quest has resulted in enormous repositories of genealogical information that Mormons have collected from around the world and brought back to their headquarters in Salt Lake City. Today, much of it is available in scanned, searchable form on sites such as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.com.

I was raised Unitarian-Universalist, the uber-liberal religion that shudders — shudders, I tell you! — at the idea of “teaching” a particular gospel to anyone, living or dead.

And yet the impulse to understand my family’s roots probably comes from the same place for me as it does for the Mormons and people of so many other faiths (and non-faiths): a desire to have some kind of retroactive relationship with my dead ancestors.

This desire may be especially compelling in a country such as the United States, where so many of us have lost touch with our roots and where the ideal has long been to assimilate, to “start all over again” without the encumbrances of the Old World’s oppressive dogmas and political structures.

While that attitude has some clear benefits, it’s also contributed (for me, at least) to persistent feelings of disconnection. I want to know more about these long-ago people whose existence led to mine. I want to know in what ways they struggled and triumphed and simply muddled through, and how their actions and decisions (whether skillful or unskillful) might echo in mine.

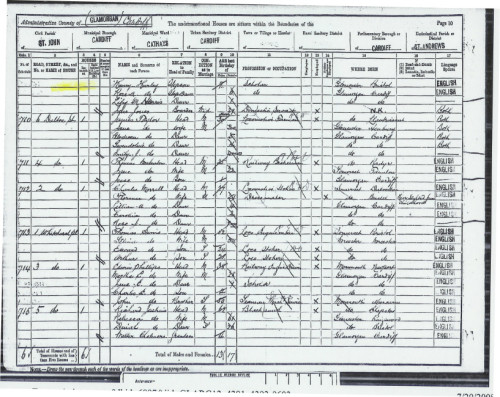

The strange intimacy of Census documents

Ancestry.com contains U.S. Census documents from 1800 until 1940 (the release of more recent documents being considered an invasion of potentially living people’s privacy). Documents from other countries, including England, are also online.

The information they provide strikes a strange kind of balance between dryness and intimacy.

You won’t learn how people looked, of course, or how they talked. But you’ll learn what they told Census takers about what they did for a living. Who their spouses and children were. Where they were born.

Then there’s the charm of the documents themselves. With their cramped rows of handwritten lines, it’s easy to picture the conversations that would have taken place to create them. The Census taker moving door to door, asking personal questions about what went on behind the walls of ordinarily private houses and scribbling those answers into their ledgers.

There’s a vulnerability about it all, facades stripped away to reveal the bare facts of a life.

In the case of the Glanvilles, here’s some of what I saw in the Census documents from England:

Occupation: Agricultural labourer.

Birthplace: St. Pinnock, Cornwall.

Parents’ birthplace: Variously reported as St. Pinnock or St. Neot or Lanteglos.

Number of children: 6. With workaday names such as Jane and John and James.

These are not the details of prosperous or mobile or easy lives — though they may have been happy ones.

In the first days of my research, as I pulled up document after document, I was able to construct the outlines of a story. The great thing about Census documents is they’re just specific enough to paint a picture that you can supplement with historical research.

Knowing exactly when and where an ancestor was born, for example, invites you to look into the social, economic and political conditions of that time and place. If an ancestor hit U.S. shores in the last century or so, you can even look up the weather on the day they arrived.

Sometimes, my imagination ran rampant. Positively Poldark-ian, really.

The Glanvilles were poor farmers heroically surviving off Cornwall’s thin, granite-choked soil! Maybe they were even serfs working for a strict but beneficent overlord! (Never mind that, in the late 19th century, we’re a few centuries too late for serfs.)

Here, then, is my best effort to reign in those tendencies, recounting what those ancient Census busybodies could tell me while adding a little geographical and historical research of my own — otherwise known as Googling around.

The Glanvilles and Cornwall in the 19th century

My great-great-grandfather, Richard Robert Glanville — the first of my Glanville ancestors to come to the U.S. — was born on April 19, 1853 in St. Pinnock, a tiny farming village in southeast Cornwall.

It was beautiful if lonely country, composed of deeply cut hills, a couple of churches (one of them Methodist, on which more later) and a picturesque railroad overpass called the St. Pinnock Viaduct. The Viaduct would have been under construction when Richard was born, and opened the following year.

Even today, fewer than 700 souls call the town home.

St. Pinnock lay in the shadow of Bodmin Moor, an ancient granite upland spiked with tors (granite outcrops), stone circles and Neolithic tombs.

This eerie landscape was the legendary stomping ground of King Arthur. By some accounts, the lake from which the Lady of the Lake offered Arthur Excalibur was Dozmary Pool.

Richard was the second of six kids, and the oldest son of James and Jane (nee Roberts — the likely source of Richard’s middle name).

James’ birthplace was variously reported to the Census as Warleggan (haha yeah! The name of the villain in Poldark!), St. Neot or St. Pinnock. His birth year was 1827 or 1828. Since the earliest, parent-reported birthplace listed on the 1841 Census is St. Neot, let’s go with that. Plus, the Rough Guide to Devon and Cornwall calls it one of Cornwall’s most charming towns.

Jane was a year older than James. She’d been born in Lanteglos-by-Fowey, a town on Cornwall’s south coast that was the adopted hometown of du Maurier.

All of these places are within spitting distance from each other in southeast Cornwall, which speaks to a time when people were a lot less mobile.

James came from a farming family himself. He lived at home until the early 1850s, helping with his own parents’ farm, when he married Jane.

It’s unclear from the Census documents whether the newlyweds farmed their own land or worked on someone else’s. James’ occupation is listed as “agricultural labourer,” a humble-sounding title that seems to imply he worked where and when needed. (His own dad, John, had reported the same occupation.)

But a little digging brought me to this document about 19th century occupational titles used in the English Census, which explains:

“[T]hose giving the occupations ‘Farm Servant’ and ‘Agricultural Labourer’—obviously different occupational titles—might be classified together under the heading of agricultural workers. In this case, in the late-nineteenth century at least, people giving themselves either of these two occupations would be performing a similar economic function, the main difference being that the former would generally be employed under a formal contractual arrangement which included living on a farm in which they worked whereas the latter would have been living in a distinct property.”

In other words, James and Jane lived on property they farmed themselves, though whether or not they owned the land isn’t clear. (Nor, unfortunately, is their exact address.)

James, Jane and their growing family — six kids born between 1852 and 1866 — likely lived a hardscrabble existence, one that got harder as the years pressed on. It wasn’t just the number of mouths they had to feed, though that couldn’t have helped. The second half of the 19th century was particularly tough economically for Cornwall.

Cornish mining: The end of an era

For millennia, going back as far as 2150 B.C., tin and copper mining was a primary driver of the Cornish economy.

But by the mid-19th century, mineral reserves had been dwindling for decades. When new, richer mines were discovered in Australia and South Africa in the mid-1800s, the local mining industry took a huge hit. The crisis was exacerbated by a collapse in copper prices in 1866.

Every decade between 1861 and 1901, one in five Cornish men emigrated, more than triple the rate for England and Wales overall. Between 1841 and 1901, Cornwall saw its population decline by 250,000 people — a mass exodus called the Cornish Diaspora.

If anything, farming in Cornwall offered an even more tenuous — if less physically dangerous — existence than mining. The same ancient volcanic upheavals that metamorphosed the region’s rocks, creating rich mineral deposits, also resulted in thin soil over poorly drained granite.

The long, maritime-influenced growing season partially compensated, but many Cornish farmers raised livestock rather than try to coax crops from the paltry soil. As miners fled during the 19th century, farmers would have suffered by extension, losing a huge chunk of their customer base.

What was Richard Robert doing during this time? During the 1871 Census, the last one before he came to the U.S., he would have been 17 or 18. Interestingly, his occupation is listed not as agricultural labourer, which I would have expected given that he was still living at home with farmer parents. Instead, he was a “domestic labourer,” which probably means he did odd jobs around other people’s houses. Had work on the farm dried up to the point that James no longer needed him?

If so, the reason for Richard’s emigration would seem to be obvious. Picking up work where he could, likely slogging away in poverty, he couldn’t have seen very bright prospects for his own future in Cornwall. The defection of thousands of his peers to the New World would only have heightened a sense of urgency to get out while he was still young, able-bodied and childless.

QED, right? He books passage to New York. Starts a new life. That’s that.

Except… that wasn’t that.

The real reason he left was a young woman. Her name was Mary Keast.

Next time, I learn more about Mary — and what the young couple’s life was like once they landed in America.

4 Comments