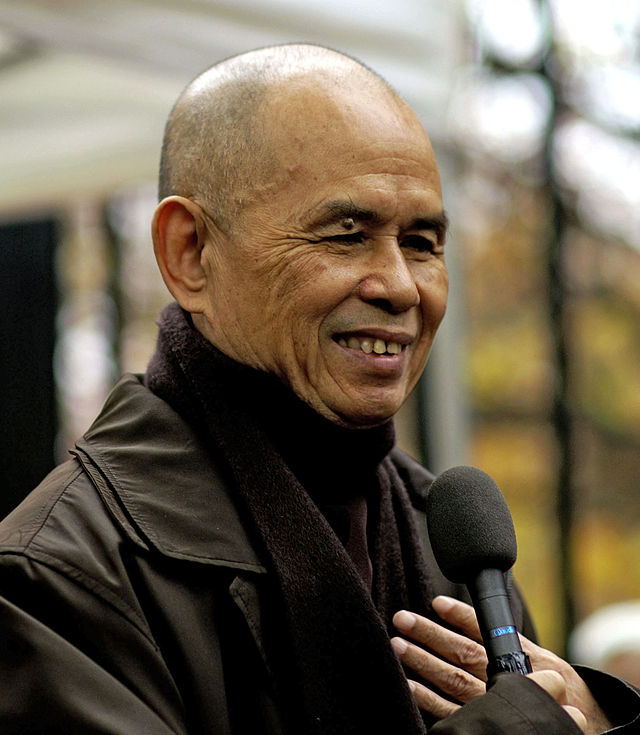

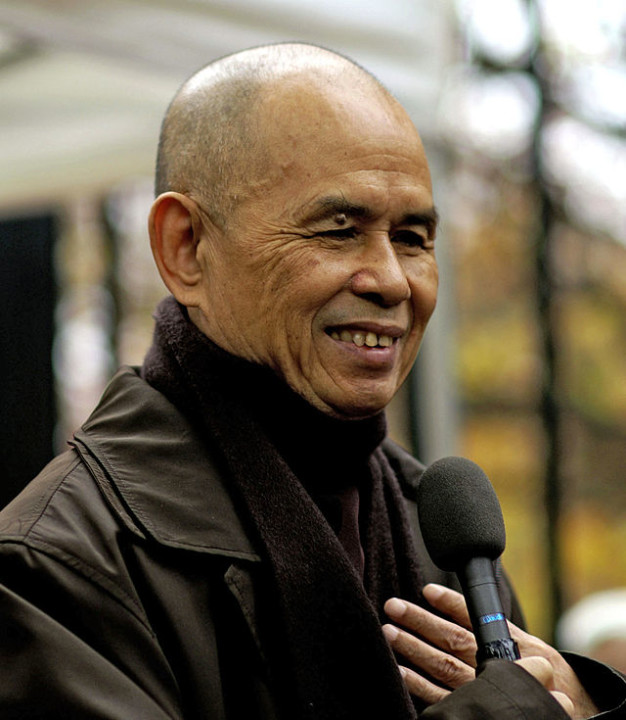

Beloved mindfulness teacher and Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh is slowly recovering in a French hospital after suffering a major brain hemorrhage last week. I’ve been lucky enough to attend a few retreats with him and/or his monastics at Blue Cliff Monastery in upstate New York! Below are my humble thoughts on the uniqueness of his teaching style.

The first time I saw Thich Nhat Hanh in person, he was wearing a huge brown knit cap.

It wasn’t a very nice cap. It was the kind of cap, actually, that you’d expect to find in a thrift store sales bin, along with a thousand others like it, pilled and stretched thin.

The cap made him look even shorter and thinner than he is — which is pretty short and thin. So did his monk’s robes, also brown. As he walked toward the meditation hall that early morning, he looked no larger than the dozen or so children who followed along behind him.

Yet there was no denying the magnitude of his presence. He seemed to calm everyone and everything he walked past. The birds sang legato. The tree branches stilled.

And of course, none of the hundreds of retreatants who joined him on that chilly August 2013 morning at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, spoke a word. We were all silent — gladly so. After all, this was why we’d come: to slow down. To stop.

The sight was surreal: five hundred or more people walking at a glacial pace, not speaking. Occasionally, a summer student at the university would rush past, backpack slung over shoulder, hurrying toward some computer lab or library, a reminder of how quickly we usually move.

I stood at a remove from the crowd, watching as much as participating.

There was a strange mix of genuineness and tourism to the scene. On the one hand, everyone was by definition practicing mindfulness — the Buddhism-derived principle of slowing down and paying attention that Thich Nhat Hanh had been instrumental in popularizing in the West. We were being quiet, we were moving slowly. We were listening to sounds we otherwise wouldn’t hear. I can still remember the collective whisper of a thousand pant legs hushing against each other, the patter of footsteps.

On the other, people were aiming phone cameras. Snap snap — wait, here’s a better angle. And every one of us stared, no doubt hoping to acquire or at least consume some of the peace the man exuded.

Maybe, I thought, this was one of the outcomes of Westernizing mindfulness. Put into an American context, mindfulness becomes something we think of as a commodity. Something we can purchase by attending a retreat or buying a book.

What did he think, I wondered, about all the cameras and the staring? Was he judging us all for missing the point, forgoing the genuine, in-the-moment experience to make a record of it?

To judge from his gentle smile and placid face, no. He was not judging.

I think this is Thich Nhat Hanh’s genius. More than perhaps any other teacher of Buddhism and mindfulness in the West, he is willing — no, happy — to start from where his students actually are, not from where he thinks they should already be. That’s what all great teachers do. They speak the language of the student. They take responsibility for the learning that’s supposed to happen. They find a way to transfer wisdom — or better yet, experience — rather than merely convey it.

Yes, it’s easy to dismiss Thay — the Vietnamese word for “teacher,” as his students know him — as peddling a kind of Buddhism-Lite, a defanged New Age mush for the masses. He writes his books in plain, heartfelt language, free from the lists and scriptural citations that make the work of many of his peers such a slog for casual readers. When he speaks to the media, he avoids technical terms and even avoids the term “Buddhism” itself. (His in-person lectures, by contrast, are quite intellectually rigorous — perhaps with the rationale that students who reach the point of attending a lecture are ready for something deeper.)

And OK, those criticisms are fair in a way, though I think there’s often intellectual snobbery and even a level of machismo there. Much of Thay’s imagery and language is feminine — references to flowers and birds, exhortations to refer to oneself as “darling.” So is his soft, quiet way of speaking.

Still, it’s true that you will probably not Learn Buddhism in the strictest sense from reading Thich Nhat Hanh.

But where I think he excels is in teaching busy, numb Westerners how to slow down, pay attention and feel.

If the way to get there is through cameras snapping, so be it. At least they were starting. At least they were trying. And in being patient with all that, of course, he models one of the basic precepts of Buddhism and indeed most religions: compassion.

#

A few minutes after the walk that morning, we were all seated in a big lecture hall. Thay sat in the middle of a stage, flanked by huge banner-printed photographs of himself. These, too, made me squirm, seeming more appropriate to a rock concert than a dharma talk. “Yes, you are really here!” they seemed to say. “This is really him!”

But then Thay started speaking — softly, as usual, so that you had to perk up your ears to hear. He talked about ancestry, and the karmic passing of hurt from one generation to the next. He talked about how we as adults have the opportunity to transform that hurt. He suggested how we could do it, in language that encouraged us to be compassionate toward ourselves and our families.

Within about 20 minutes, my cynicism about phone cameras and spiritual materialism had evaporated. None of it mattered, because here were words that somehow encompassed all the complexity and sadness and joy of life itself.

For a few precious moments, I’d been freed from thinking. I could simply feel.