Today I gave in to being a tourist. Temporarily, I think, because ultimately I like exploring things better on my own. But it also was kind of relaxing just to ride around in buses all day, allowing a tour guide to herd me from place to place.

Seth and I woke early and found that our hostal — like many in the Peru highlands — keeps a nice pot of fresh coca leaves on the breakfast table. I regarded the leaves, my old teetotaler tendencies welling up, maybe fearing I’d become a Stevie Nicks-style, lost-my-nose-septum crackhead if I partook.

“How many leaves should I put in?” I asked the hostal owner.

“Oh, six or seven,” she said. She took the tongs from me and transferred about 20 into my cup, then poured in hot water and told me to let it steep for a while.

When my cocaine drink was ready, I sipped it curiously. Within a few minutes, my head — which still felt clogged, tight — seemed to warm and expand, my brain releasing from the grip the altitude had on it. Seth, meanwhile, was sipping the stuff like an old pro. He’s been drinking coca for a day or two, since he’s already traveled through Cusco.

Mildly revved after breakfast, we waited for our tour bus to show up for the trip to Lake Titicaca and the Uros Islands. I caught a whiff of myself. Somehow, since arriving in Puno, I’d started to smell like patchouli, even though I couldn’t remember having been around any incense. It was as if the mystical, hippy vibe of the place was manifesting itself as a smell.

The next 30 minutes were a blur of tourism at its most stressful. Our tour bus jockey hurried us onboard, not even allowing me to go back to my room for aspirin. (Not for my head but for a sour neck from lugging my ever-heavier backpack.)

We went around the city for a few more minutes, picking up tourists from their hostals. A sour Italian woman in the front seat kept muttering about “idiotas” who didn’t have enough respect to be ready on time. She was also unhappy with the traffic.

“Muy traffico,” she complained to the driver, whom she’d been vaguely addressing.

“Si, mucho traffico,” the driver gently corrected her. “No te preocupa.”

Minutes later, we were at the lake shore, and filed onto a boat that looked exactly like the bus, but in the water. Seth!

A guy with a guitar and pipes boarded and started to play an Andean version of The Beatles’ “Life Goes On.” A moment of confusion when he thought the boat was about to leave, and then, realizing it wasn’t, he soldiered on.

“Welcome especially Peru,” our guide said when the song was over. Every other word was “no.” That seems to be a Puno verbal quirk. “We go to the Uros Islands, no? In Lake Titikhaaakhaaaa…” This was a point he really wanted to drive home: only clueless people pronounced the lake’s name “Titicaca.” The c’s are actually pronounced like the guttural “ch” in challah bread. He’s probably sick of Titicaca jokes.

The boat roared to life and we were off. Between his not-so-great English, my mediocre Espanol, and what I’d read beforehand, here’s what I learned about the Uros Islands: They are more than 50 of them, all built from the reeds growing in the lake. To make their islands bigger, or to repair “holes,” the people stack the reeds on top of each other, creating a mat 2-3 meters thick. Something like this:

There are more than 70 tiny islands, each home to a small number of families. In all, about 2,300 people live in Uros. The islanders mostly speak a dialect of Quechua, and started building these islands in the lake when their traditional homelands to the south began to be occupied by the Inca and later colonial Spanish.

We glided through natural marshy areas of reeds, and then into the more open water where the islands are built. They made an otherworldly sight, a whole world of two colors and textures: water and reeds. Seemingly everything that wasn’t part of the lake was made of the reeds: the islands themselves, of course, but also the houses and boats.

We motored up to one of the islands, called Titino (which means cougar), and some moms and kids were waiting to greet us. I’d read that Uros has become quite the tourist attraction in the past couple of decades, so I wasn’t surprised that we got the full-performance welcome.

Here’s the way the island looks as it floats in the water — you can see the cross-section of reeds.

We stepped out, and it felt something like walking across a giant straw waterbed. Titino supports six families and 25 people, and has a male leader who looks to be in his mid-30s. Women’s dress corresponds to whether they’re married (colorful) or single (wildly colorful). The guide talked about how the islanders eat lots of fish and birds, which are readily available, but they have to go to the mainland to trade for produce. Another staple of their diet is the same reed from which their islands are built. We got some to try, and it tasted like a milder, softer version of celery.

Next came a very touristy series of presentations about traditional Uros dress and bargaining practices. The guide gestured to an older woman wearing full brightly colored costume; she stood, eyes downcast, as he talked. I shifted uncomfortably. Who was being exploited here? Us or the islanders? Both? Is it OK that they’re supporting themselves at least partly through our curiosity, which we satisfy by buying tours and their craft items? Is some part of their culture being damaged, or is it being sustained through a new source of revenue? The old, uncomfortable questions of cultural tourism.

We got into a traditional boat made mostly of reed and with cougar-heads on its bow. Two of the islanders paddled us to another island, about 15 minutes away. Seth and I sat in the precarious upper part of the boat, Seth crammed into a corner next to the impatient Italian — who’d mellowed, thankfully — and two Brazilians. Despite the crowdedness of the boat, it was a tranquil and calming ride, gliding through this world of reed and water.

Once we arrived back at the bus on the mainland, a couple of young Puno women who worked for one of the bus companies wanted their pictures taken with me, Seth and a solo traveler we’d met named Mike. We must have looked American, or at least foreign. OK, definitely mutual exploitation.

Mike, who’s in med school and studying ethnobotany, told us he was on his way to Cusco not only to hike Machu Picchu but to take part in an ayahuasca ceremony. Ayahuasca is a wildly strong hallucinogen that has been used by the indigenous people of the Andes for centuries as a way of cleansing the mind of old fears and anxieties. For the past few decades, white people have been seeking it out, too. It causes some of the most nightmare-like visions known to man, but many people report that their lives are transformed and they become more fearless afterward. Others aren’t so lucky. I’ve considered doing it myself, but I’m not quite there yet. Mike has promised to report back his results.

In the afternoon, we joined another tour, with the same guide, to Sillustani, a pre-Incan city of the dead about 45 minutes outside Puno, right on Lake Titicaca.

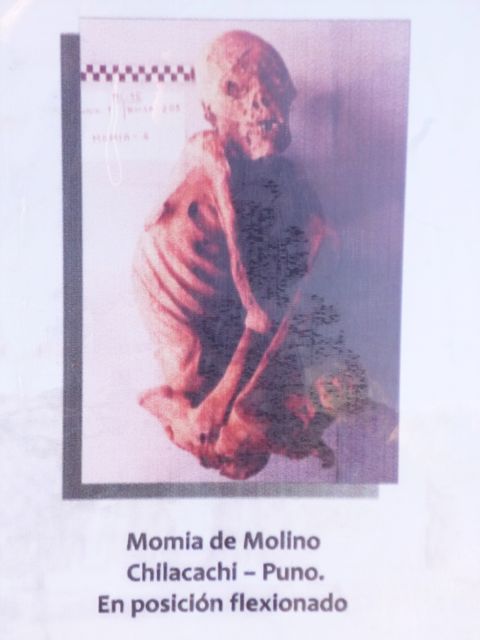

This was a culture known as the Colla people, obliterated by the Inca in the 15th century. They buried their dead in graceful stone towers showing some impressive masonry skills.

The most important people were buried at the top of the hill, in this white-stone tower.

This stone is not indigenous to the area and must have been carried from far away. The dead were buried with great quantities of gold jewelry and objects. As in ancient Egypt, tombs also contained food and drink to be used in the afterlife.

There’s a relief sculpture of a lizard on the exterior of the tower, probably a symbol of one of their gods. You can see it in the photo below, on the block about halfway down and all the way to the right.

Commoners were buried in smaller, native-stone towers at the bottom of the hill.

Everyone, royal and common, was buried in a cramped fetal position. All towers had a small entrance at their base, through which the living made offerings to the dead. Here’s how the mummies looked!

The guide warned us that sometimes strange things happen at this site, such as tourists’ cameras suddenly running out of batteries. We all smiled. But sure enough, a couple minutes later, Seth announced his camera was almost dead. It had had two bars of energy before we started the walk. WEIRD….

Here’s the ruined “back” half of the tower. Most of the towers were destroyed by grave robbers many years ago.

The Inca used the site even after they smashed the Colla. They built a few more towers beyond the Lizard Tower, and these are in excellent condition. Even better, though, are the views of the lake from this area:

For dinner, Seth and I met up with Mike and ate chifa — the hybrid Peruvian-Chinese food I’d so enjoyed my first evening in Arequipa. The restaurant we went to was called Chifa Shanghai, across from the Mercado Central, and it was packed to bursting with Peruvians, which we took as a good sign. Sure enough, the food was excellent, and I ordered a shrimp-vegetable stir-fry that contained even more vegetables than had my gringo salad.

Afterward, we went to pay our bill at the hostal. The owner told us they could only accept cash, despite the confirmation email that said they accepted credit cards. Irritated, I had to march back down the steep hill to the Plaza to get cash. These little moments of travel disempowerment are interesting, so typical of travel especially in foreign places. Or maybe it’s not disempowerment as having to give up a bit of the control you’re used to. You’re not from here, and there’s less you can control as a result.